Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

Positive long-term outlook for Irish Agriculture

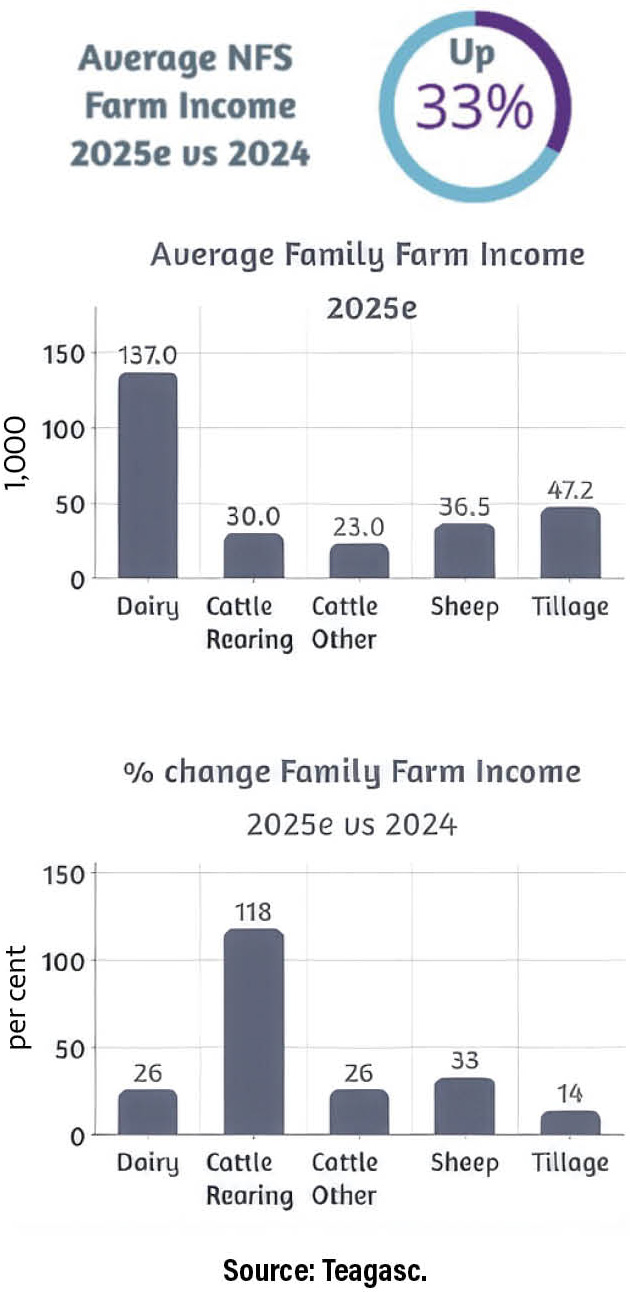

The chart below from Teagasc’s Outlook 2026: Economic Outlook for Irish Agriculture report, shows an increase in farm incomes last year of 33 per cent, with beef farming delivering the largest percentage increases in incomes at 118 per cent.

Unfortunately, 2026 does not look as promising, particularly for the dairy and tillage sectors. Based on current market trends, Teagasc predicts on-farm milk prices, particularly during the production peak, of 42.4c/L. Nevertheless, the overall Irish economic contribution of the primary agriculture sector looks like being sustained.

A multiplier impact

Indeed, the Central Statistics Office (CSO) early estimate puts the overall value of agricultural output for 2026 in excess of €13.5bn which, with known CSO multipliers, puts Irish economy expenditure for the food production sector in excess of €20bn. Early indicators of export value put total food and drink exports in 2025 at €20bn, despite direct Trump tariff threat impacts and consequent global trading challenges.

This is clearly and unambiguously a huge and very real contribution to the Irish economy supporting over 220,000 jobs in farming, manufacturing and distribution, making the sector very relevant to the Irish economy in 2025 and into the future. Moreover, the yield from increased agricultural output value represents a unique impact in the Irish economy and a footprint that is driving real Irish economic transactions.

In terms of Irish expenditure within the Irish economy, (a much more sober /realistic measurement of the impact of local and multinational companies in the Irish economy than delusional gross value-added calculations), the agri-food sector constitutes one third of all industry spend.

Global competence

At the core of these very impressive figures is a global competence in producing and marketing sustainable food and drink for 50 million consumers, that no other indigenous sector can come near. Moreover, this embedded competence is also testament not just to agri-industry and producers’ understanding of real global trends in demand for sustainable food, but to the Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine and its agencies for their strategies and support for the sector. This global connectivity is in direct contrast to the ‘small island’ disconnected and introverted thinking that has tried to misidentify the agriculture sector solely in terms of environmental impacts.

Moreover, the recurring and resilient, substantive and unique, economic impact of the Irish agri-food and drink sectors surely demonstrates the good fortune of having world class producers, processors and Government departments and agencies working in tandem, while at the same time hosting our world-class foreign direct investment (FDI) sectors.

To be very clear, there is no inherent conflict in supporting the development of our world class agri-food sector and, at the same time, supporting our FDI stream. But perhaps one of the first challenges for our industrial development gurus might be to recognise that our FDI companies are successfully embedded in Ireland because they are hugely incentivised.

Narrow industrial focus

Herein lies a huge challenge, though. There is no doubt, from tuning in any day to public discourse and, indeed, discussions with a broad range of non-agriculture related departments will confirm this, that in terms of industrial development policy the sole focus seems to be on the policy needs and incentives for FDI.

At the same time, there is concern in the agricultural sector that its cost challenges are not understood, and, possibly as importantly, are expected to be absorbed when its output is effectively constrained. The competitiveness challenges facing the agri sector, including the huge cost of decarbonisation for processors and farmers, are clearly substantial. But, unlike the energy sector for example, there is absolutely no discussion of guaranteed long-term pricing incentives being put in place to support substantial decarbonisation costs. Likewise, in terms of access to the competitive ‘patient capital’ required, there seems to be no interest at Government level in instituting a root and branch examination of current EU state aid rules to develop a bespoke support system for Ireland's largest indigenous sector.

This is in sharp contrast to a German approach that is constantly exerting political pressure to ease constraints on its capability of providing German state support for heavy industry and car manufacturing. Incidentally, at the same time, Germany is also pushing back on EU commitments to phase out non fully electric cars by 2035.

Supporting global competence

Regarding the overall competitiveness challenges facing the Irish agri sector, as has been clearly demonstrated, a combination of regulatory constraints and zero selling power means low or no possibility of recovering decarbonisation and other transition costs in the marketplace through increased prices. As importantly, Government must understand that the production limits imposed on the primary processing sectors, through environmental constraints, effectively mean that increased costs cannot be absorbed through increased output. Ireland's agri sector is a hugely important and relevant cog in the modern Irish economy wheel. The people in agri-business, from farm to fork, have enduring global competence and, very importantly, are experiencing increasing global demand for the food we produce.

Government, respectfully, needs to come on board with the agri sector and discuss a combination of supports that are specific to the challenges which the agricultural sector is facing and embracing.