Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

Boundless beef optimism

In the midst of concern about tariff wars and general economic instability, the recent surge in ex-farm beef prices has largely gone under the public radar. From a producer perspective, while the increase in beef prices is welcomed there is clear concern as to whether ex-farm beef prices have reached a new sustainable plateau or whether, as in the past, consumers switching to traditionally lower-priced substitutes such as poultry/pigmeat will see a return to previous ‘normality’.

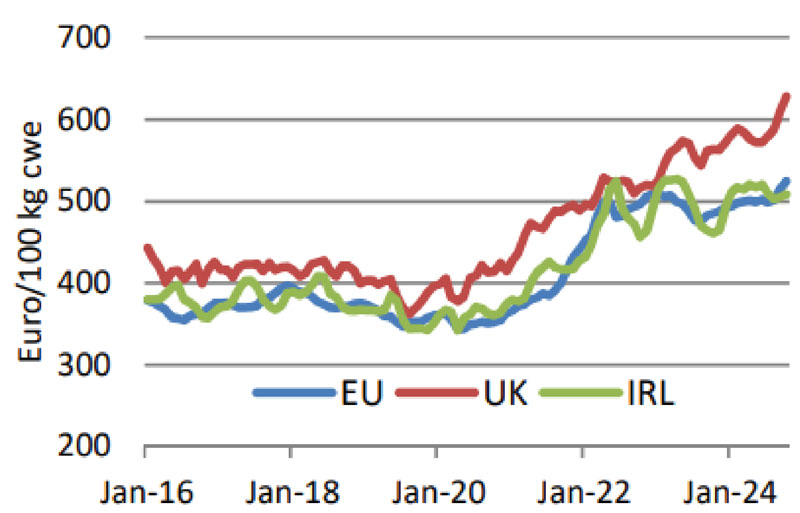

Monthly EU, UK, and Irish finished cattle prices 2016 to 2024 (excl. VAT). Source: DG Agriculture and Rural Development, AHDB, and ECB. Ireland and UK Steer R3, EU27 Young Bull R3.

Will consumers chicken out?

Indeed, 20-year consumption trend figures for both Ireland and the UK – the latter still being our biggest export market – show a steady decline in consumption of beef, more than matched by an increase in poultry meat consumption. Another concern of Irish beef producers has to be that, in the context of EU trade policy, an even more benign view of EU beef imports could see increased competition from this source.

So what does the future hold?

EU Commission figures show that both production and consumption of beef in the EU and UK are in steady decline. In a sense, the basic economics of beef production has been problematic for a long number of years with many learned Irish economists suggesting that an examination of beef farm incomes seemed to show that the more animals farmers reared, the less income they secured.

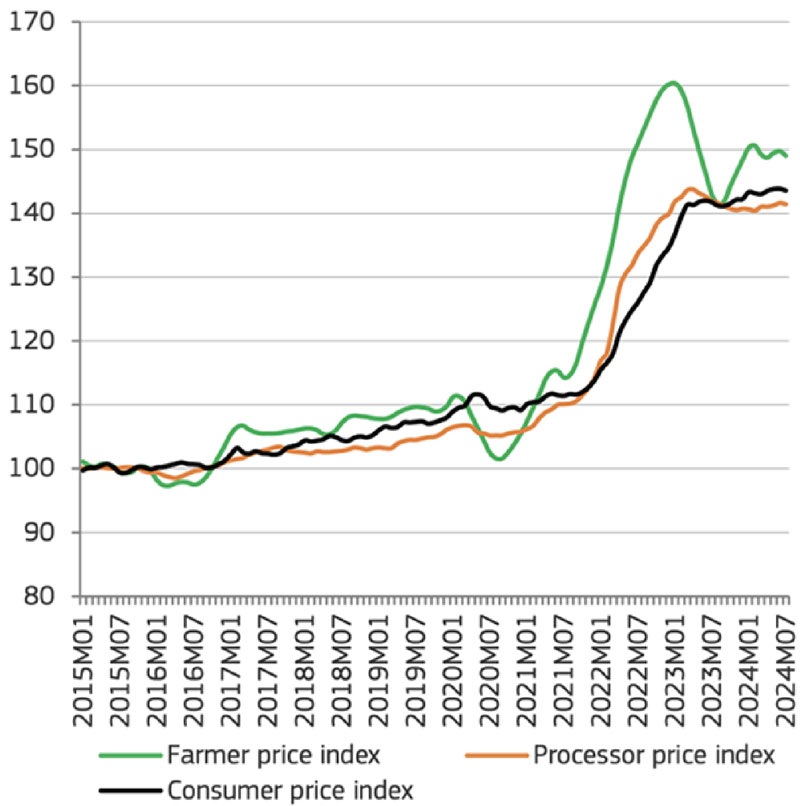

The more salient point I would suggest is that beef cattle numbers have been in fairly consistent decline for over 10 years now and the current supply/demand disconnect has been evolving over that period. In terms of price spikes, the tendency for individual food products to step out of, and back into, the pattern of overall food inflation is illustrated in the chart below from the EU’s Short-term Outlook for Autumn 2024.

Price transmission along the food chain (2015=100).

What the chart illustrates is a strong long-term (2015 to 2024) link between inflation (price changes not price levels) in consumer prices and farmer/processor prices. The spike in farmer prices in 2022 represents the surge in grain prices driven by concerns about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As the chart indicates, in the wake of the 2022 ‘shock’, producer prices stepped back into the long-term trend of following price inflation in consumer and processor price changes.

So is the current beef price hike a short-term shock and is a return to ‘normal’ pricing indicated? As previously mentioned, beef production and consumption levels are falling and continuing to decline in the EU and UK.

In Ireland, suckler cow numbers, as of the December 2024 census were just over 75,000 head, down over 50,000 year on year, but more importantly down 33 per cent or 350,000 head since the peak in 2012. Moreover, dairy cow numbers also declined in December 2024.This decline in numbers is matched by declines in carcase weights as more of our beef comes from dairy sires. This reduction in suckler cow numbers was predicted back in the early 2000s when EU direct supports were decoupled. However, it only really took off when CAP reforms saw ongoing reductions in direct supports to facilitate greening payments, and because of what might be described as stable, but low, prices up to recent years.

Widespread production decline

This reduction in production of beef is mirrored across the EU and, more importantly, in the UK (still Ireland’s biggest market), with the slight nuance that most EU countries did not see the increase in dairy cow numbers that we had in Ireland since the abolition of milk quotas. But a number of key EU beef-producing countries, including France, Spain, and Austria, maintain a coupled beef suckler cow payment and have not seen the dramatic fall off in beef cow numbers that Ireland has experienced without a coupled payment.

In many respects, numbers-based economic analysis of supply and demand trends does not of itself provide a clear rationale as to why, with both consumption and production in decline, beef prices in Ireland and the UK have surged. One interesting possibility is a change in medium- to-long-term pricing policy by EU/UK supermarkets with beef now being reclassified as a non-loss-leading item. As we know, supermarkets stock over 20,000 stock-keeping units (SKUs) and clearly have huge flexibility as to where in the basket of consumer purchases of up to 150 items the supermarket makes its profit.

Consumers back beef

Another thought that might support the notion above is to conclude that beef consumers in the UK/Ireland and across the EU were largely deaf to the ‘noise’ about reducing beef consumption as part of a climate change mitigation initiative. Here again, the disconnect between actual consumer concerns and the weaponisation of IPPC accounting rules might shed some light. Under IPPC accounting protocols, emissions from beef production are accounted for in the country of production (Ireland), not the country of consumption (UK/EU), while emissions from fossil fuels – coal and oil – are accounted for in the country of consumption. So, for international customers of Irish beef in the UK and EU, beef consumption is not considered, under IPPC accounting protocols, an emissions-related behaviour.

Worn down by criticism

Beef consumption and the beef industry have demonstrated huge resilience in the past, most notably in the aftermath of the BSE scare in the late 1990s. For many beef producers in Ireland, the UK, and across Europe, however, the hostile background noise, attempting ultimately to characterise beef as a fossil fuel, allied to ever more repressive regulations and production restrictions, seem to have been the last straws in causing them to decide to exit the sector in large numbers.